Imitating Nature is a Rigorous Practice: An Interview with Curator Linda Tesner

Since the turn of the 20th century, there have been significant artistic moments in which artists have sought to mimic the forms and patterns of nature in glass. Field Notes: Artists Observe Nature explores specimens of work from the Art Nouveau period to the contemporary. With works by Vittorio Constantini, Joey Kirkpatrick, René Lalique, Flora C. Mace, and William Morris, among others, Guest Curator Linda Tesner has gathered an array of glass flora and fauna, ranging from vessels with applied hot-sculpted pinecones, to birds drawn in glass powder on glass pages, to intricately flameworked, entomologically-accurate glass insect specimens. The exhibition opens November 16, 2024.

Ice Blue Vase with Oak Leaves and Acorns, 2004. Dusted vessel, applied oak boughs, engraved leaves and acorns. 13 1/2 x 8 3/4 x 7 3/4 in.

Museum of Glass: What led you to the concept for Field Notes?

Linda Tesner: In my long-ago graduate school days, I specialized in Northern Renaissance art. Part of my attraction to that era had to do with the way artists represented nature, something in which I have had a lifelong interest. Beloved and long-held visual touchstones for me are images such as Jan and Hubert van Eck's details of lilies and iris in Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (the Ghent Altarpiece; 1432) or Albrecht Dürer's Two Squirrels (1492) in the Albertina in Vienna. Think of the cave paintings of animals at Lascaux! Artists representing nature is a theme as old as time. I love the tradition and continuity that is suggested by contemporary artists in this subject matter — the assiduous adherence to realistic representation or intentional deviation thereof, the palpable sense of marvel that these artists experience in the natural world, and the emotive potential in natural history subjects. The ideas represented in this exhibition have been rattling around in my head for a very long time.

MOG: How did you select the artists for the exhibition? What qualities did their art have that made their work fit with the show's theme?

LT: There are many, many artists that are inspired by nature, of course, and that inspiration manifests in innumerable ways. An artist might abstract a flower form as a decorative motif or invoke a bird for its metaphoric content. These are fascinating ways to evoke nature, but, in the case of Field Notes, I am interested in artists for whom imitating nature is a rigorous practice. These artists are essentially citizen scientists in their commitment to reproducing elements of nature as accurately as possible. Vittorio Costantini is an excellent example of this. He is a serious student of the insect world; his glass insects are so accurate that they are essentially enduring entomological specimens.

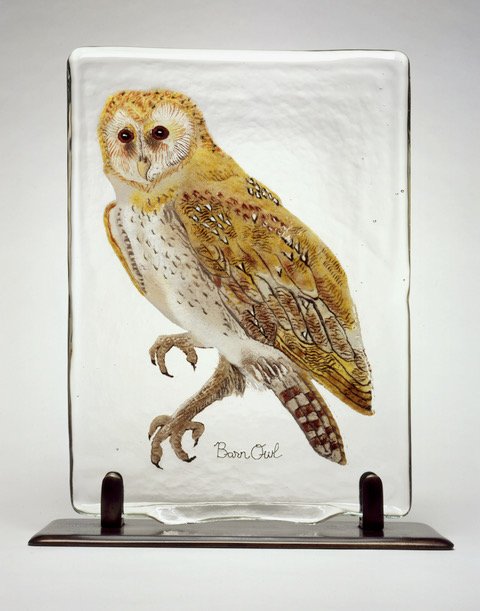

The early impetus of Joey Kirkpatrick and Flora C. Mace's Bird Pages had to do with birdwatching from their studio on a canal in Ballard. Kirkpatrick had been a lifelong birder and, as an aid to assist Mace in identifying specimens, she made bird sketches to be used like flash cards. This led to their incredibly technical achievement of Kirkpatrick "drawing" birds in glass powder to be picked up on a "page" of glass, a unique process devised by Mace. One of the goals of the Bird Pages series is to capture both the “first facts” and the “jizz” of each bird. The “first facts” are those attributes that identify a bird: its shape, colors, movement, sounds, and so on. The “jizz” is a more subtle form of bird identification. It implies the attitude or personality—the “isness”—of a specimen that makes it possible for an experienced birdwatcher to discern a specimen in the fleeting seconds of a sighting or from a great distance.

Joey Kirkpatrick (American, born 1952) and Flora C. Mace (American, born 1949). Bird Page: Barn Owl, 2004. Glass and steel. 17 1/2 x 14 x 6 in. Courtesy of the artists

Malia Jensen. Hand with Plum, 2020. Kiln-cast glass. 7.5 x 10.5 x 8.5 in.

Malia Jensen's work involves both observing animal behavior via video cameras located in nature, and then literally collaborating with deer and other mammals in the making of her sculptures. In her series Nearer Nature, she made sculptures out of salt blocks, which she placed at various locations in the wilderness. As animals licked the salt, they reshaped Jensen's sculptures, which Jensen eventually cast into glass. Jensen's work is perhaps the most exaggerated example of an artist whose work is deeply invested in the natural world to the point that non-human species were her collaborators. Nonetheless, each artist in Field Notes: Artists Observe Nature has an intimacy with natural history that is particularly noteworthy.

MOG: How do you think glass as a medium lends itself to the topic of wildlife and nature differently than other mediums?

LT: That is such an interesting question. I think one could say that the history of scientific illustration has its roots in drawing and painting. I might go so far as to say that early 19th century artists such as Émile Gallé depended upon exquisite draftsmanship, along with sculptural modeling, to recreate accurate images of flora and fauna. Gallé's skillful use of cased glass and cameo glass is, in effect, a version of drawing.

The Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants –the famous “Blaschka Flowers” by the father-and-son team of Leopold and Rudolph Blaschka, located at the Harvard Museum of Natural History – may be the first example of the use of glass to accurately depict living specimens in three dimensions. In addition to botanical specimens, the Blaschkas crafted glass invertebrates and educational models of non-flowering plants and fungi from a microscopic viewpoint. It is fascinating to me that glass was the medium to make the leap from two dimensional scientific illustrations to three dimensional models of specimens. Why not ceramic, or metal, or some other sculptural material, like paper pulp? I wouldn't say that glass is the only or best way to recreate specimens of natural history, but there is certainly a strong tradition in that regard. The permanence of glass, the methods of achieving color in glass, and the inordinate manipulability of glass are qualities which lend themselves well to representing nature.

Work by Émile Gallé and René Lalique (middle). Photo courtesy of Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, WA.

William Morris (American, born 1957). Vase with Wren and Berries, 2004. Dust-drawn berry bush, applied boughs, engraved leaves, berries, and bird. 10 x 8 3/8 x 7 1/2 in. The George R. Stroemple Collection, A Stroemple/Stirek Collaboration.

MOG: The artwork in this show spans more than 100 years. What are the similarities and differences between the works of different eras?

LT: One of the things I love about glass as an art medium is that it is both ancient—think of Roman glass vessels—and completely contemporary. Glass is extraordinary in terms of malleability, limited only by the artist's abilities and vision. Using traditional glass methods, each artist adapts the intrinsic qualities of glass to explore various themes; very often, contemporary artists build on traditional techniques to achieve new results. Think about how Lino Tagliapietra's early traditional Venetian goblets evolved into Dale Chihuly's exuberant and monumental Venetians. This exhibition includes both blown and flameworked glass, pâte de verre (Amalric Walter), enamel drawing on glass (Deborah Horrell), hot-sculpted glass, glass "pages" made by a fairly traditional printmaking technique (the Kirkpatrick and Mace Bird Pages), drawings in layered glass powder (William Morris), and more. All of these processes are steeped in tradition but bent to the vision of the artist. In my view, there are more similarities between the historical artists and contemporary artists than there are differences, but I would be very open to hear from others who disagree with that perspective.

MOG: Tell us about the background behind the creation of the insects by Vittorio Cosntantini.

LT: Oh, my gosh. Meeting Vittorio Costantini and his wife, Graziella Giolo, and helping George Stroemple develop his collection of glass entymological specimens has to be one of the most treasured experiences of my professional life. I have had the privilege of working with George Stroemple for the better part of twenty-five years. Many years ago, while looking at the Alexis Rockman painting Evolution, George directed my attention to the numerous insects included in the painting. George had heard that there was an artist in Venice who made highly realistic glass insects, and he asked me to figure out who that artist was and inquire about his interest in creating insects that are included in the painting—a sort of exercise in popping two-dimensional painted insects into sculptural objects.

That was in the very early days of the internet, but I eventually figured out that it was Vittorio Costantini who made glass insects (as well as birds and butterflies). I emailed him to inquire about a commission. I think I might have even initiated our conversation by fax! Vittorio was enthusaistic about the idea, but he had one strict caveat: his insects are so fragile that he insists that they are hand-carried out of his studio. They should never be shipped because the hair-like antennae and legs would be so apt to break. So, the condition of the commission was that I would "have to" go to Venice to select the insects, then hand-courier them back to Portland, Oregon. Vittorio's studio is deep in the heart of the Cannaregio, a quick vaporetto ride from both Murano and Burano, where Vittorio was raised. (I like to think that the lacemaking traditions of Burano are parallel to the "knitting" of glass in Vittorio's lampworking.) During the day, I would select and photograph glass specimens to email to George, then, in the evenings, we would discuss George's final selections. I think I made four or five trips to Venice, carrying back a modified camera case full of insects as carry-on luggage on each trip. In all of those trips, we never had a single glass specimen break, which is a tribute to Vittorio's expertise. It used to take a full day for Vittorio to pack the specimens, buttressing each attenna and leg with tiny bolsters of cotton batting.

Eventually, George amassed a collection of about 350 insects, many of which are magnum opera of Vittorio's career. This exhibition is only the second time that this collection has been seen in public! I'm so excited for them to be on view in the Pacific Northwest.

Vittorio Costantini (Italian, born 1944). Entomological Specimens. Hot-sculpted glass. The George R. Stroemple Collection, A Stroemple/Stirek Collaboration.

Alexis Rockman. Evolution, 1992. Oil on wood. 96 x 288 in. From the George R. Stroemple Collection.

Joey Kirkpatrick (American, born 1952) and Flora C. Mace (American, born 1949). Snipe Daffodil, 2021. Flower, composite, glass, and steel. 22 3/4 x 18 x 7 in. Courtesy of the artists.

MOG: What do you hope Museum visitors will take away from this exhibition?

LT: I have no agenda for the visitor, other than to experience historical and contemporary art that is exquisitely crafted and inexhaustibly beautiful. My most fervent wish is that visitors will leave with a sense of wonder, more than anything else. If that happens, then I would consider the exhibition to be a success. If the exhibition triggers other responses—say, an emerging artist is inspired to try a new technique, someone is reminded to visit their local botanical garden or hang a bird feeder, or a patron is moved to donate philanthropically to a conservation effort—well, that's a bonus!

MOG: The definition and background of “curator” has changed a lot in recent times. What do you see as the role of curator today?

LT: That is such an interesting question, one that museums must face and discuss with their constituents. I'm an older curator. I admit to having been trained in the pedagogy of largely outdated museum methods. I am absolutely an object-based curator—the way an object is made and its context are essential to me. I have always thought of a curator as akin to an essayist—exploring a theme or concept with visual material. I think and hope that this is still rele

vant, but I appreciate that the role of curator is now more readily shared with individuals or collectives who are not steeped in traditional museum modalities. I welcome the redefinition of "curator" as it expands to represent broader means of observing and understanding art. We don't want museums to become mausoleums of antiquated ideas. This requires often uncomfortable dialogue and experimentation in which the museum is more of a laboratory than a temple.

MOG: Why is it important that this exhibition is organized by and exhibited at Museum of Glass?

LT: I don't know of many museums that are exclusively dedicated to one medium. The fact that Museum of Glass, the Corning Museum of Glass, and the Toledo Museum of Art's Glass Pavilion exist is a testament to how broadly this medium is interpreted, and speaks confidently and optimistically toward a future of unknowable experimentation and exploration in glass. Field Notes: Artists Observe Nature could just as well be an exhibition on the various uses of glass as a medium to explore a theme in historical and contemporary examples. I greatly appreciate that I was invited to include some artwork in the exhibition that is not glass—the Blaschka botanical drawings, the Alexis Rockman painting, Joey Kirkpatrick's bird drawings, Malia Jensen's time-based video—because I don't see glass as a medium siloed from other disciplines. I am very grateful to Museum of Glass for allowing me to bring these particular artists and their work into one space, and I hope that the experience of the exhibition will generate interesting conversations.

William Morris (American, born 1957). Footed Specimen Bowl, 2004. Glass with applied desert artifacts. 6 7/8 x 16 1/2 x 16 1/2 in. The George R. Stroemple Collection, A Stroemple/Stirek Collaboration.

Photo courtesy of Linda Tesner.

About Curator Linda Tesner

Linda Tesner is Guest Curator for Field Notes: Artists Observe Nature. Tesner is former director and curator of the Ronna and Eric Hoffman Gallery of Contemporary Art at Lewis & Clark College, Portland, Oregon. Previously, she was assistant director of the Portland Art Museum and director of the Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, Washington. She is the author of numerous exhibition catalogs and monographs. Tesner now curates a private collection. In 2015, Tesner was the guest curator of the exhibition, Joey Kirkpatrick and Flora C. Mace: Every Soil Bears Not Everything, authoring the companion exhibition catalog for Museum of Glass.