Double, Double: The Use of Glass in the Donmar Warehouse's Production of MACBETH

By Bryn Cavin, Marketing & Content Manager

If you spend much time amongst the curatorial staff at Museum of Glass, you’ll inevitably hear them paraphrase Bertil Vallien’s quote, “The glass is an invisible material that eats the light and forwards it.” This fancifully witchy mindset has managed to haunt me outside of Museum hours and follow me all the way to the West End, where I had the absolute honor of watching glass devour light – among other things – in an entirely different way from how it does in our galleries, from the second row of the Donmar Warehouse.

This past November, two of my similarly Shakespeare-smitten university pals and I found out that David Tennant was to star in the Donmar’s upcoming production of Macbeth – for which all tickets had already been sold – and so, naturally, we booked an entire trip to the United Kingdom about it. We flew to London in the first week of January with naught but our carry-on luggage and our vaulting ambition, in the hopes of maybe, possibly, perhaps getting into this fully sold-out show. Through tenacity, perseverance, delusion, and an absurd level of commitment to the bit, we lucked into a set of returned tickets to a Saturday matinee.

Bryn, overcome by the proximity of the stage and the very fact of having gotten tickets to the show, observed by fellow PNW museum professional and friend Amber Van Brunt. Photo by Monika Hash.

Cush Jumbo and David Tennant featured on the title page of the play program. All hail, dastardly king and queen of my heart hereafter.

Truly, it was even more breathtaking than I could have anticipated. The movement direction? Stunning. The sound design? Delicious. The line delivery from every member of the cast? Lives in my bones now. I will be thinking about this production daily forevermore, so if anyone would like to have an English major-y shouting session about every detail of it, let me know.

One of those most scrumptious of details was the stark staging of the play. The set consisted of only the bright white central stage, the aisles around it, and a boxy black space behind the stage, which was separated from the stage and audience by three panes of glass. The optical properties of the glass allowed it to become a powerful storytelling element, serving almost as a character in its own right. Because of its transparency, reflectivity, and apparent impermeability, the glass acted as the boundary between the corporeal and supernatural elements of the play, and simultaneously created both an illusion of distance from and a physical record of the violence done by Macbeth in his pursuit of power.

David Tennant and Cush Jumbo as Macbeth and Lady Macbeth (Macbeth Act 2, Scene 2). Courtesy of the Donmar Warehouse. Photo by Marc Brenner.

The glass established itself as intermediary between the physical and the otherworldly from the first moment of the play. Through Gareth Fry’s binaural soundscape, the Weird Sisters’ whispered chorus of the opening lines seemed to come from every side. In fact, they came from a row of black-clad members of the cast seated behind the glass, looming in the darkness like a series of disembodied heads. Centerstage, outside of the glass, a bloodied Macbeth sat before a mirrored silver basin of water, washing his hands, face, and neck clean after battle with the traitorous Thane of Cawdor. In back of Macbeth, the glass captured his reflection, layering his translucent double over the witches behind it. By being at once reflective and transparent, the glass imposed a clear boundary between the two realms at play, but allowed the audience into both realms at once. At times throughout the play, the characters behind the glass would pound with their palms or knock against it to try to attract Macbeth’s attention as he began his descent into tyranny. At others, they would watch his every move, keeping their eyes firmly on him and embodying his paranoia. At the same time, every character who walked in front of the glass was doubled in its reflective surface, creating a ghostly version of each, which served at first as a foreshadowing of what was to come and later as a reminder of the consequences of Macbeth’s and Lady Macbeth’s actions.

In addition, the glass acted as a means to create distance between Macbeth and the violence enacted to maintain his power after his murder of Duncan and usurpation of the kingship. Following Macbeth’s possession of the crown, as his paranoia about Banquo’s knowledge of his deeds grew, Lady Macbeth became frustrated with his withdrawnness, in spite of what she viewed as their success. She attempted to confront him about his behavior, facing the audience as Macbeth faced away, looking into the glass. In his reflection, his eyes were distant from her, focused on himself or on some otherworldly middle distance during their conversation:

LADY MACBETH: How now, my lord, why do you keep alone,

Of sorriest fancies your companions making,

using those thoughts which should indeed have died

with them they think on? Things without all remedy

Should be without regard, What’s done is done.

MACBETH: We have scorched the snake, not killed it.

She’ll close and be herself whilst our poor malice

Remains in danger of her former tooth.

But let the frame of things disjoint, both the worlds suffer,

Ere we will eat our meal in fear and sleep

In the affliction of these terrible dreams

That shake us nightly. Better be with the dead,

Whom we to gain our peace, have sent to peace,

Than on the torture of the mind to lie

In restless ecstasy. (3.2.10-25)

To hear Macbeth’s “But let the frame of things disjoint, both the worlds suffer” but not to be able to see his face directly, seeing it only in translucent reflection within the frame which acted as the border between those two worlds, added an extra layer of hauntedness to Macbeth’s already bedeviled contemplations.

When Macbeth ordered Banquo and Fleance killed, Banquo’s murder took place out of sight but a blood-soaked Fleance – Banquo’s young son – pressed close to the glass, crying, to look down on Macbeth before running away and escaping the cutthroats, putting the first crack in Macbeth’s plan to snuff out all threats to his rule.

As the story progressed, the rigidity of the glass boundary began to break down. When Macbeth returned to the witches to learn how to keep his kingship secure, the cast lined up behind the glass as they had in the beginning, speaking in the same chorus of whispers. But, when they reached the line “Open, locks, whoever knocks,” the actor playing Malcolm, having in this moment become part of the ensemble of witches, slid open the leftmost pane of glass to reveal a doorway. The witches, played by nearly every member of the cast, spilled out to surround Macbeth as they summoned the three apparitions to speak to him. Later, during the attack on Macduff’s wife and children, Macduff’s son escaped from behind the glass through the doorway, running across the stage and into Macbeth, standing at its front corner and fastidiously cleaning his fingernails. Without a flicker of change in his expression, Macbeth silently caught the child and dumped him into the arms of a cutthroat, who carried him, screaming, out of sight. The breaking open of the glass boundary by the witches was the catalyst for the first directly violent action that Macbeth took in full view of the audience, rather than out of sight or through proxy.

Our final glimpse of Lady Macbeth was as the doctor and gentlewoman stood behind the glass to observe her walking about with a candle, and talking both to herself and to an invisible child, in her sleep. First walking behind the doctor and gentlewoman in the enclosed glass space, Lady Macbeth then climbed down onto the central stage, making her candle gutter with the change in the air. From the central stage, she was again reflected from behind and in profile by the glass, so that the audience saw at once corporeal and ethereal versions of her, each with her own candle as she repeatedly attempted to clean her hands. With her final lines –

To bed, to bed. There’s knocking at the

gate. Come, come, come, come.

Give me your hand. What’s done cannot be undone. To bed, to

bed, to bed. (5.1.69-72)

– Lady Macbeth grasped the hand of the invisible child and climbed through the glass doorway, erasing her reflected duplicate, crossing behind all three panes to make her last exit.

Cush Jumbo as Lady Macbeth (Macbeth Act 5, Scene 1). Courtesy of the Donmar Warehouse. Photo by Marc Brenner.

Macbeth learned of his wife’s death standing in the doorway of the glass, positioning him in the midst of the two realms just as Lady Macbeth had been in her final scene. Slumped to his right, he leaned his head and shoulder against the glass frame as he spoke the lines:

She should have died hereafter.

There would have been time for such a word.

Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow

creep in this petty pace from day to day

to the last syllable of recorded time,

and all our yesterdays have lighted fools

the way to dusty death. (5.5.20-26)

Upon reaching “Out, out, brief candle!,” he sank to a seat on the glass door’s threshold to speak the speech’s final lines while sitting directly upon the line that his ambition had led him to spend his whole story crossing:

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

that struts and frets his hour upon the stage

and then is heard no more. It is a tale

told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

signifying nothing. (5.5.27-31)

(Tennant’s delivery of this monologue was shattering. It’s been playing on loop on the inside of my eyelids since I left the theater.) The glass immediately mirrored Macbeth’s words by reflecting the messenger who entered the central stage from an aisle door to tell Macbeth of Birnam Wood’s arrival at Dunsinane, creating a literal walking shadow in the moment. That Macbeth was seated between this world and another, between the physical and the supernatural, and on the glass border that had separated him, for a time, from his bloody actions, as he learned of the manifestation of a portent of his coming downfall captured a perfect snapshot of his doom by the witch-spoken narrative.

In addition to creating a tangible line to be crossed, the glass was also the only element of the staging that collected the physical evidence of violence throughout the play. Although Lady Macbeth was dressed all in white, her clothing remained clean, even when she bloodied her hands returning the daggers that Macbeth had used to kill Duncan to the dead king’s room. Similarly, Macbeth changed into new clothes or cleaned his skin whenever he was marked with blood. The glass, though, became increasingly smudged with handprints from the pounding and knocking. When Lady Macduff and her children were killed by Macbeth’s cutthroats, she was pushed up against the center pane of the glass entirely by her murderer. Her handprints and an imprint of her face remained there for the rest of the play.

Rona Morison and Alasdair Macrae as Lady Macduff and Murderer (Macbeth Act 4, Scene 2). Courtesy of the Donmar Warehouse. Photo by Marc Brenner.

(Never will I ever shut up about Noof Ousellam’s delivery of “All my pretty ones?” in front of these imprints – goodness gracious.)

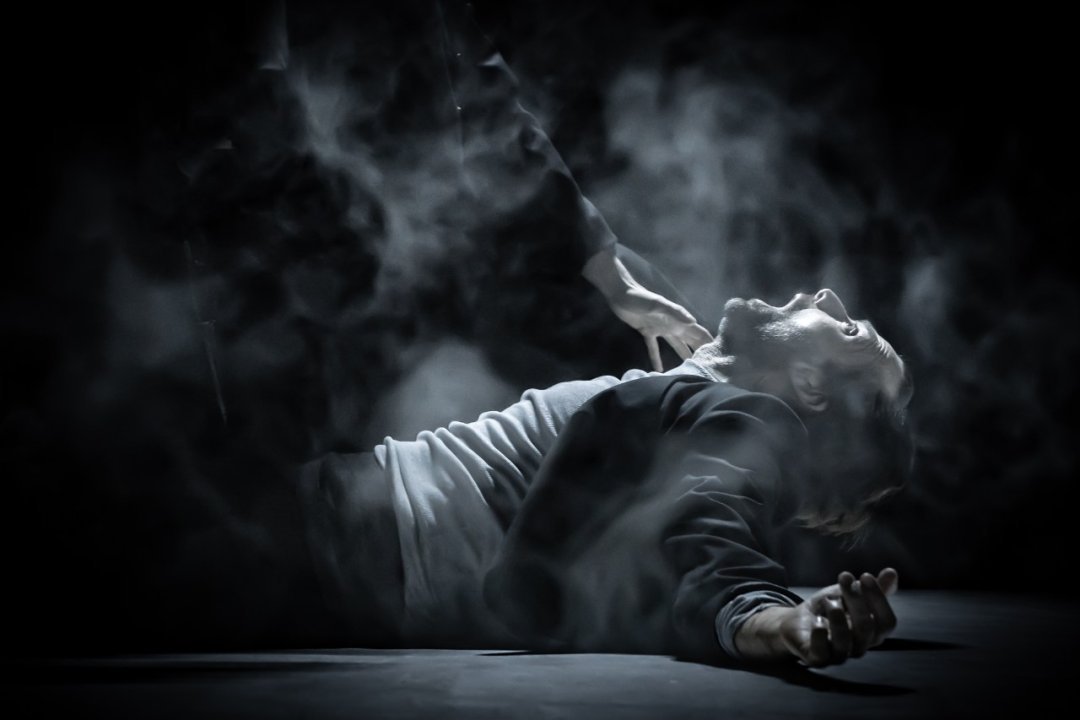

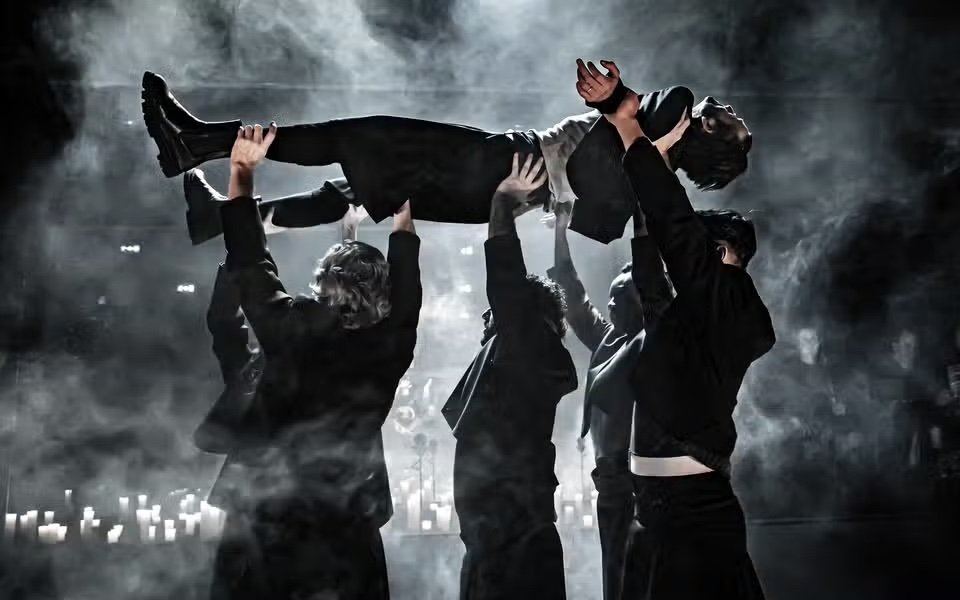

At times, the movements of the characters onstage mimicked the optical properties of the glass, acting as mirrors of their earlier selves and one another. When Macbeth was received by Duncan in thanks for his success in battle against the former Thane of Cawdor, whose position he then took on, Macbeth lay flat on the ground before Duncan, arms spread wide in the position of a cross and face turned to his right, gazing blankly into the audience. Later, when Macbeth, now king and desperate to remain so, returned to the Weird Sisters to be shown the three apparitions, the company of witches shoved him to the ground on his back and then lifted him into the air, in both positions with his arms again spread in the shape of a cross.

David Tennant as Macbeth (Macbeth Act 4, Scene). Courtesy of the Donmar Warehouse. Photo by Marc Brenner.]

David Tennant as Macbeth with the company of witches (Macbeth Act 4, Scene). Courtesy of the Donmar Warehouse. Photo by Marc Brenner.]

In Macbeth’s final scene, confronted with the knowledge that Birnam Wood had in fact arrived at Dunsinane and his challenger, Macduff, was “from his mother’s womb untimely ripped,” Macbeth shed any dignity that he had left. Having disarmed Macduff in false confidence, Macbeth held two swords, one with the blade pointed up and the other pointed down, with his arms again spread crosswise. Upon learning that Macduff was not properly a “man of woman born,” though, he threw down both swords, saying “I’ll not fight with thee.” However, goaded by Macduff’s “Then yield thee, coward,” Macbeth rushed at Macduff without a weapon and began trying to provoke him into attack by slapping Macduff’s face and pounding against his chest, mirroring the way in which the other characters had slapped and pounded on the glass wall, marking it with their handprints. When Macduff did finally strike his killing blow, Macbeth sank to the ground on his back – again in the same crosslike position – and remained there in a pool of his own blood as Malcolm inherited the kingdom, as intended by Duncan, even after all of Macbeth’s scheming. Falling where he did, Macbeth ended his story in the same place on the stage where he had begun, with his blood pooling in the same place where the mirrored basin had sat as he washed himself clean of blood in the beginning – thereby mirroring that in which he had been mirrored.

Noof Ousellam as Macduff (Macbeth, Act 5, Scene 8). Courtesy of the Donmar Warehouse. Photos by Marc Brenner.]

David Tennant as Macbeth (Macbeth, Act 5, Scene 8). Courtesy of the Donmar Warehouse. Photos by Marc Brenner.]

After Macbeth’s fall, the lights went briefly out into a total blackout. When they came up again, the branches of Birnam Wood were pressed up against the glass, lit from behind in such a way that the light filtered through the panes so that it looked like sunbeams. Lit this way, the reflectivity of the glass was mitigated, erasing the overlay of ghostly doubles that had been present up to that point and hiding the hand and face marks that had been left on it throughout. The tree branches pressed flush with the apparently clean glass broke its power as a boundary between realms, the natural overwhelming and subsuming the supernatural. The green of the trees behind it was the first new color to appear on the stage – everything up to that point had been in grayscale, occasionally bloodied – altering the atmosphere altogether to the feeling of a new morning, post-tyrant.

The stage after the cast had taken their bows and exited. Photo by Kendall Cavin.

At Museum of Glass, many of the visiting and exhibiting artists talk about how the ubiquitousness of glass often means that it goes unnoticed in its everyday contexts. In this staging of Macbeth, that omnipresent everyday-ness made the characterization of the glass as the shatterable shield dividing the physical realm from the supernatural feel all the more threatening. I will be proclaiming the Donmar gospel to all and sundry for the rest of my days. All hail to Max Webster and the brilliant minds of the cast and creative team.

Bryn, Amber, and Monika post-bewitchment.